The Museum & Grounds are now closed to the public.

We will open for tours during the Presidents Day holiday week, February 16 – 20th.

John Hays Hammond Jr.—known as “Jack” or “Jacky” to friends and family—was born April 13th, 1888 in San Francisco, California, and was the second son of successful mining engineer and investor John Hays Hammond Sr. and socialite Natalie Hammond. Throughout a remarkable career, Hammond Jr. would become one of America’s most prolific inventors, earning colorful nicknames such as “The Father of Radio Control,” “The Father of the Guided Missile,” “The Wonderful Wizard of Gloucester” and “The Electronic Sorcerer.”

A precocious mechanical mind from a young age, stories from John Hays Hammond Jr.’s youth are filled with accounts that suggest the man he would become. A fine Swiss clock meticulously disassembled by a ten year-old Jack to his mother’s horror; an adolescent Hammond founding a chemistry class ‘Anarchists Club’ and nearly leveling a school building while experimenting with high explosives. Later in life, an adult Hammond recalled a childhood visit to Thomas A. Edison’s Menlo Park laboratory with his father, and wondered at both Edison’s accomplishments and the inventor’s enthusiasm in taking time away from his busy schedule to give the Hammonds a tour.

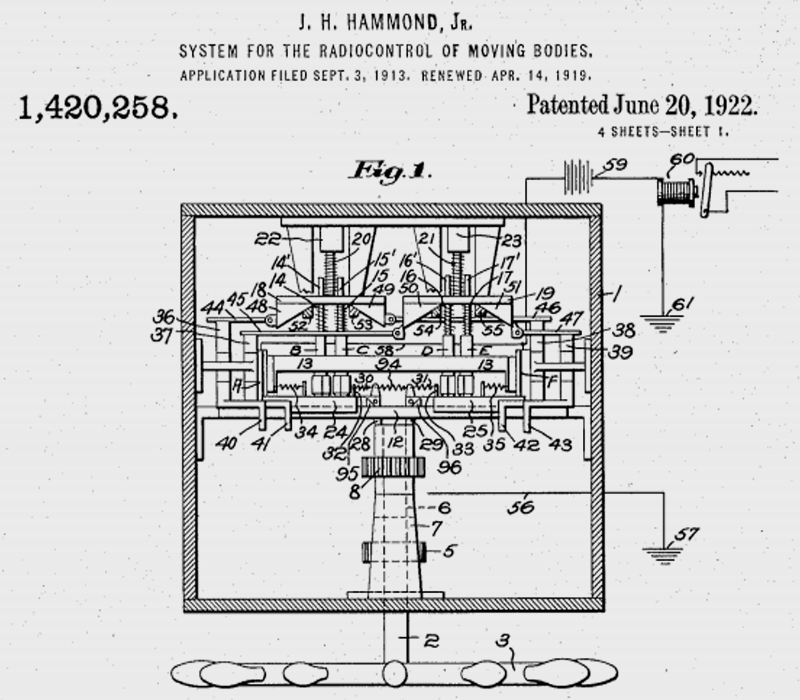

After enrolling in Yale University’s prestigious Sheffield Scientific School in 1906, Hammond Jr. would also come to be mentored by both Alexander Graham Bell and Nikola Tesla. Bell in particular was influential to the development of Hammond’s early career. When, around 1912, Hammond completed a two-year survey of foreign and domestic patents in the field of radiodynamics and loaned a copy to Bell, it was the Scottish-born pioneer who submitted the study to George Washington University as a kind of thesis on Hammond’s behalf, earning the then-recent college graduate his Doctorate of Science (Sc.D).

In 1914, just 16 years after Tesla had wowed crowds at Madison Square Garden’s 1898 Electrical Exhibition by remotely controlling a toy boat in a small pool, a 26 year-old Hammond successfully piloted a full-sized ship, The Natalia, from Gloucester to Boston and back using only a series of radio antennae on the shore and the help of an on-board stabilizing device which he called a “Gyrad”.

Widely renowned as an “inventor’s inventor,” Hammond’s diverse contributions to radio control, navigation, audio reproduction, telephony, musical instrumentation, television, acoustics, and consumer appliances, among dozens of other disciplines, are the basis for some of the most defining innovations of the 20th century. He performed extensive classified work for the United States military, and was on the board of directors of the Radio Corporation of America, better known as RCA, for 42 years.

Hammond’s lifetime achievements in radio control would earn him many accolades, including the prestigious Elliott Cresson Medal in 1959, the Franklin Institute’s highest accolade, and the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers’ (IEEE) Medal of Honor in 1963.

Despite these career accomplishments, Hammond was always remarkably prescient about the possibility that his work as inventor would not be long remembered due to the rapid pace of technological innovation. “An inventor is carving his ideas on a stream of water” Hammond reflected in a 1931 interview.

Yes, the walls of the Hammond Castle Museum housed the laboratory belonging to “the Father of the Guided Missile” during an era defined by the Space Race and Cold War, a man whose accomplishments tangibly continue to shape the cultural, technological, and political world in which we live, yet these were not the accolades that Hammond anticipated nor intended to be the foundation of his legacy.

John Hays Hammond Jr.’s true genius is most evident in that he designed the Museum not as a fabulous, meticulously-curated monument to himself, but rather as a profoundly living, and lived-in space that celebrated time and human achievement on the grand scale of history.

It is part Romanesque keep, part Gothic cathedral, part Renaissance château— it contains a collection of ancient artifacts dating as far back as the reign of Trajan—and yet it is also a place where Greta Garbo and Ramon Navarro might have danced as George Gershwin played a piano enhanced by a fourth pedal of Hammond’s own design, a place where men and women discussed both the movement of the stars and humanity’s destiny among them, and a place where countercultural poets and artists of the early 1960s drank fine champagne and talked before the fireplace late into the night.

Should Hammond be remembered as a mad scientist? A collector of antiquities? A patron of the arts? A practical jokester? A Gatsbyesque host of wild parties? An electronic sorcerer?

In reality, Hammond was none of these things, all of them, and more—for all his eccentricities, intractably, remarkably, and profoundly human, and at the Hammond Castle Museum this legacy continues.