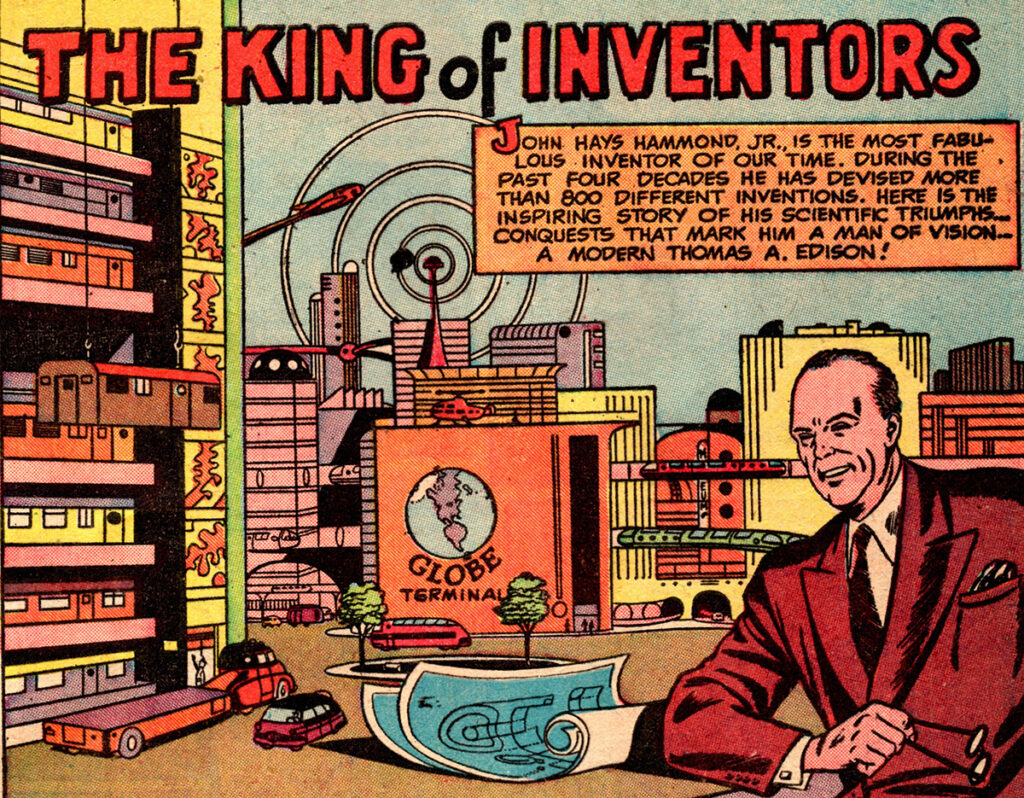

Hammond in Comics

Bruce Wayne, Clark Kent, and... John Hays Hammond Jr.?

What do these three men have in common, you might ask? Well, all of them have made appearances in the pages of DC comic books!

DC Comics has such an extensive and storied history that it would be well beyond the scope of this article to detail in full, but John Hays Hammond Jr.’s inclusion in one of the famous publisher’s books was the indirect result of an extended period of controversy in the early American comic industry during the early postwar period.

"Seduction of the Innocent"

Prominent critics such as Sterling North and Fredric Wertham, a children’s author and a psychiatrist, respectively, lambasted the popular comic books of their time, and their criticisms were influential. They believed that comic books were a corrupting influence on young minds. Everything from juvenile delinquency to teenage promiscuity was blamed on comics, along with a host of other salacious (and often preposterous) suggestions about the ideas popular titles supposedly promoted.

These barbs were not only aimed at the lurid pulp and horror tales made most famous by EC Comics, but also by the more mainstream DC Comics and other publishers. This would eventually lead to the establishment of the infamous (and now defunct) Comics Code Authority in 1954, and a period of heavy censorship in comic books. After the publication of Wertham’s book, Seduction of the Innocent and Senate hearings on the subject, “family friendly” comics became the order of the day. For example, Batman traded his gritty and violent noir detective cases for zany science fiction adventures, and expanded his “Bat-family” to include a surrogate wife, daughter, and even a dog to deflect any accusations of impropriety in his relationship with his young ward, Robin.

It is worth noting that similar “moral panics” erupted in response to rock and roll and heavy metal music, as well as tabletop roleplaying games and violent video games in later years, so this phenomenon was hardly unique in pop cultural history.

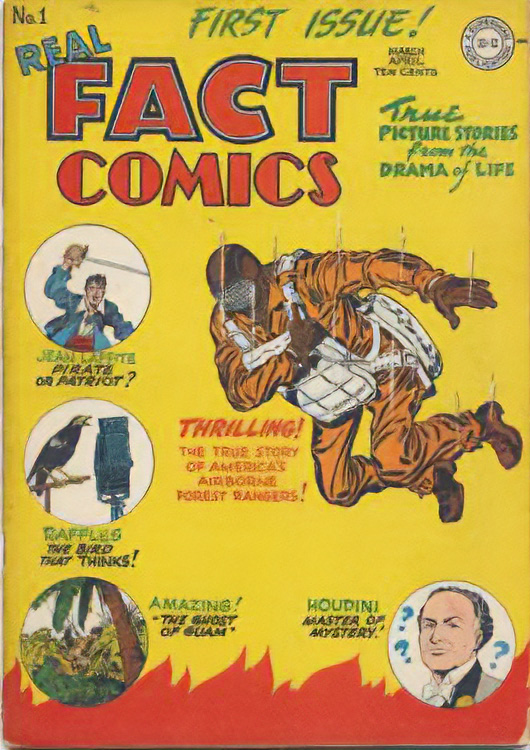

Real Fact Comics

In the 1940s, a few years prior to these sweeping reforms in comic books, DC still faced criticism and commercial challenges. Superheroes temporarily waned in popularity following WWII, and the publisher decided to experiment with a new, educational title that would include profiles of famous, real-life figures as well as supposedly “true stories” based on historical events: Real Fact Comics. They were not the first publisher to dabble in this genre, and their results were not entirely successful.

The series’ relatively short life was the result of somewhat tepid sales. Despite this, some legendary comics creators worked on the title, such as Jack Kirby, Dick Sprang, and Joe Simon.

Famous icons profiled in the comic ranged from magician and skeptic Harry Houdini to circus promoter P.T. Barnum. But issue #18 of the title from January/February 1949 presented a six-page biography of John Hays Hammond Jr. Dubbing him “The King of Inventors” and “a modern Thomas A. Edison,” (one of Hammond’s famous mentors), DC’s portrayal of the scientist was quite flattering, albeit with some historical inaccuracies.

"Real Fact" Comics?

For example, the introductory blurb credits Hammond with over 800 inventions, but the evidence from the U.S. Patent Office does not reflect this count. The most up-to-date count research indicates that Hammond held 437 registered U.S. patents, about half of what is claimed in the comic. Hammond also held at least 114 foreign patents, bringing the total to 551, but that is still shy of the oft-quoted 800 figure. An index of Hammond’s patent “case” numbers does reach into the 800s, however, and it is from here that the confusion likely arose. Like many prolific inventors, not all of Hammond’s patent filings resulted in patents being awarded, either due to him abandoning the claims partway through the process, or discovering that another inventor had beaten him to the punch. As will be discussed shortly, the likely author of this comic later penned an article on Hammond, wherein the qualifier “patentable ideas” was used alongside the number 800.

The second panel sees John Hays Hammond Sr. receiving a telegram informing him of Hammond Jr.’s birth while he was in South Africa; in reality, the inventor was already five years old by the time his father went to South Africa, and lived with him there alongside his mother and older brother, Harris.

The comic also suggests that Hammond’s father was nothing but supportive of his son’s scientific aspirations, and while it is true that his father did loan him money to begin his laboratory and was not dismissive of his career, he did occasionally have his criticisms of his son’s chosen path. That being said, the evidence available does paint a picture of Hammond Sr. as a loving and supportive father to his children overall, so his attitude is perhaps oversimplified rather than completely misrepresented in the comic.

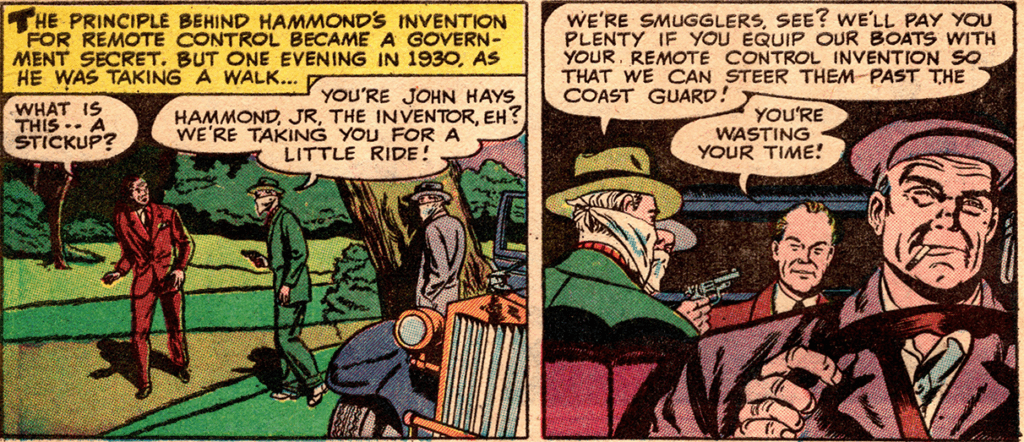

The incident with the rum runners

Another exaggerated account comes on the fourth page of the story, when Hammond is approached at gunpoint by gangsters seeking his radio-guided technology for smuggling boats. There is apparently some truth to the story, as Hammond reportedly was approached by a rum-running syndicate who hoped to buy his technology for such purposes, and he did indeed refuse, as indicated in the comic. However, this was not a forced meeting where Hammond was abducted. It is possible that Hammond either fabricated that detail himself to make the story more colorful, or that it was done so by the writer(s).

It is also possible that it was a simple error: Hammond was once mistakenly believed to have been abducted by car after a mysterious note was found that claimed to have been thrown from the vehicle by the abductee in hopes of rescue. The note was signed, “John Hammond,” but the inventor was soon discovered to be perfectly safe and accounted for, so if the note was genuine, it was written by another John Hammond. The writer(s) of the comic may have seen both news stories in the papers and conflated them.

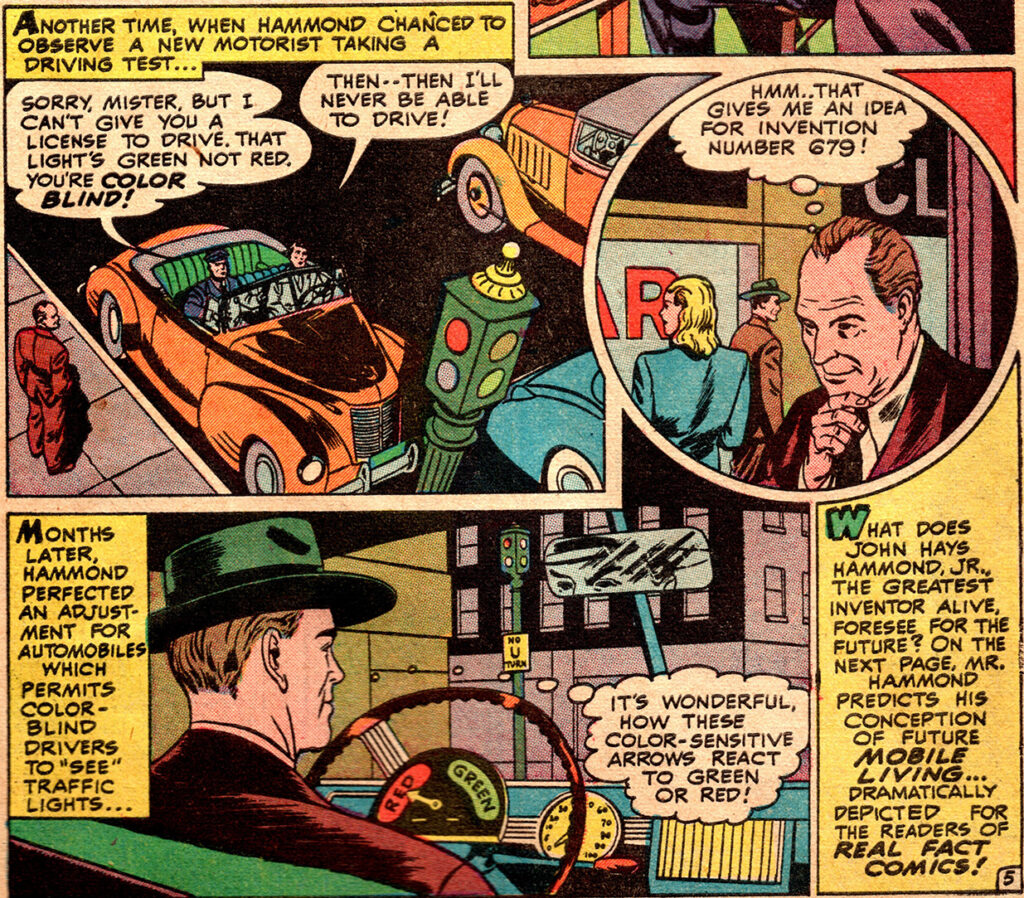

No filed patent has yet surfaced regarding the traffic light aid for colorblind motorists that appears on page five (much less identifying it so specifically as “Invention Number 679”). It is certainly possible that Hammond considered such an idea and simply never patented it (perhaps because traffic light standards were eventually codified to aid colorblind people, such as including a fixed order for the lights, rendering the idea obsolete), but the only other known mention of this invention comes from an article penned by the probable lead author of this comic.

The probable author

Myths aside, the existence of this comic biography of Hammond, alongside several other cartoon and comic strip depictions of the inventor and his inventions that appeared in newspapers and magazines, demonstrates the inventor’s celebrity status during his life. It also shows how popular culture can be used as a vessel to educate as well as entertain, the factual errors notwithstanding.

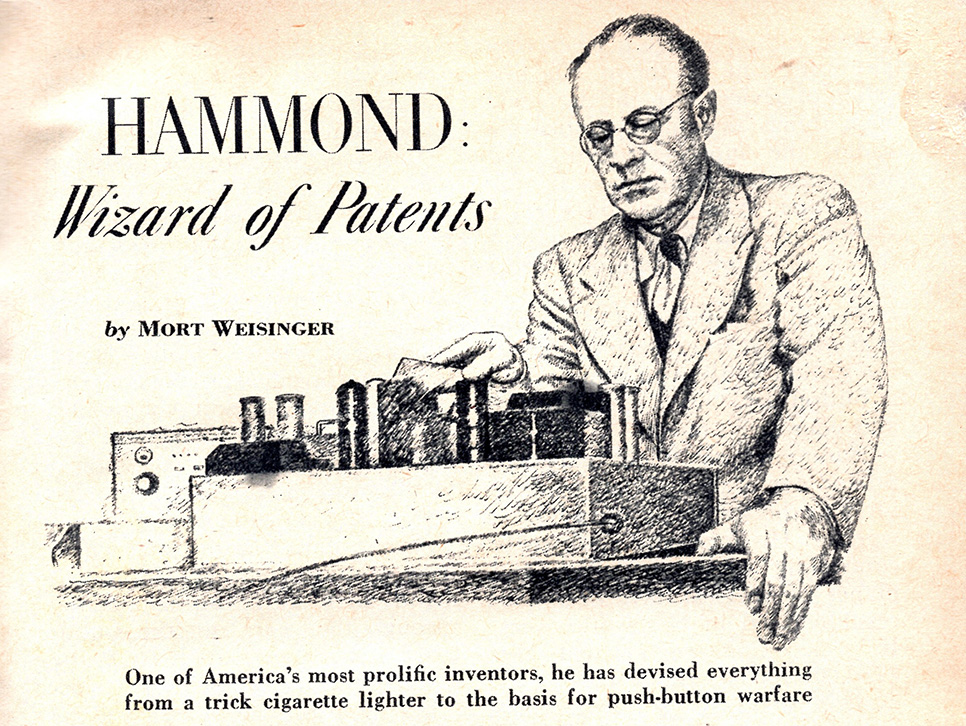

The writer of the biography, though not given a byline, was most likely Mort Weisinger. He is known to have worked on Real Fact Comics alongside other writers, and he was also the author of “Hammond: Wizard of Patents,” a profile of the inventor published in Coronet Magazine, which appeared mere months after the publication of this comic book. The article mentions many of the same inventions depicted in the comic – both real and dubious – and includes illustrations as well. Curiously, the piece also states that Hammond Sr. had been dead for fifteen years; in reality, he had only passed away thirteen years previous to its publication, in 1936. If only Weisinger had done the math, he might have avoided his timeline errors.

Artist unknown

Unfortunately, the comic’s artist is neither credited nor definitively known. Iconic Batman artist Dick Sprang penciled the cover and the lead story, “The Mystery Man of Tombstone,” but his trademark style, characterized by dynamic action and square-jawed heroes, does not seem on display in the Hammond story. Unfortunately, the early comics industry was not known for respecting or paying its artists and writers very much, and crediting them was neither universal nor consistent, especially in an anthology series like Real Fact Comics. For now, at least, the artist who depicted Hammond remains anonymous.

Watch more about the Hammond Comics.

Watch our Hammond Weekly Episode from 2022 about the Hammond Comics!