The Prisma Record

A "rainbow" record

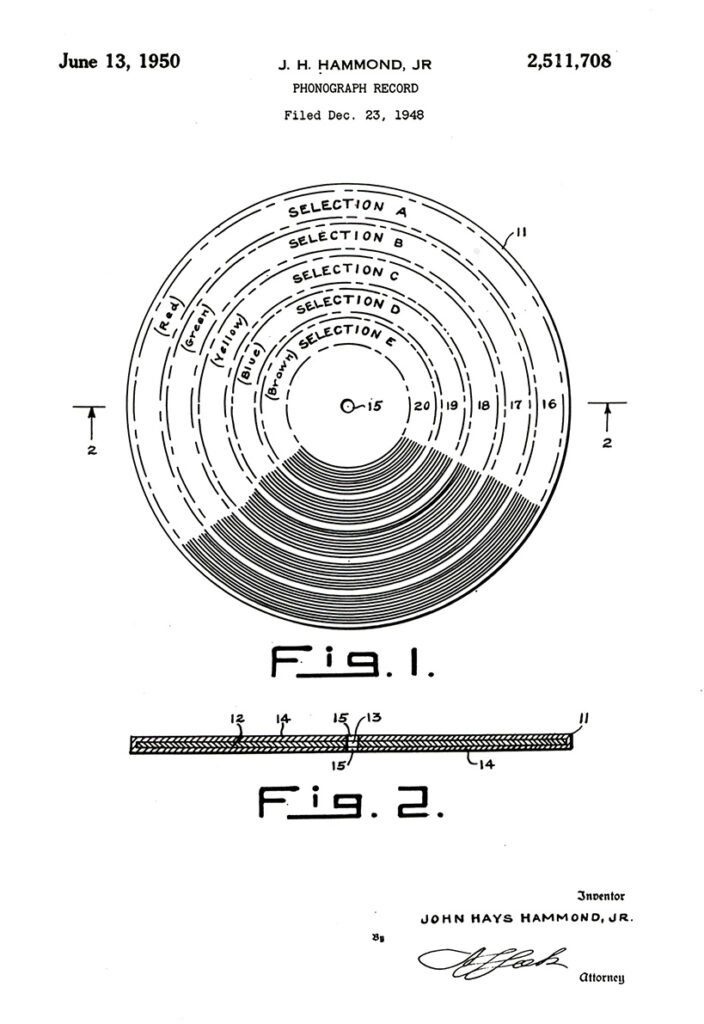

The “Prisma” Record was a rainbow-colored vinyl record designed and patented by John Hays Hammond Jr. in 1948 to solve a particular annoyance with that venerable music medium: the lack of a way to easily select a specific track to listen to on a given album.

For those who have never listened to a vinyl LP (short for “Long Play,” or a full-length album), it may be surprising to learn that there was a time when it was more common than not for music fans to listen to a complete album from beginning to end, in the order it was arranged. While 7-inch vinyl singles containing 1 or 2 tracks and 7- or 10-inch EPs (or “Extended Plays”) containing 3-6 songs are not uncommon, the 12-inch LP was the standard major music format from the 1920s through the 1980s, and has experienced a surprising revival in recent years.

A linear listening experience

While all formats of music albums can obviously be listened to in a linear fashion, doing so was the rule rather than the exception in Hammond’s time. Both phonograph records and magnetic cassette tapes were designed to be listened to from front-to-back, typically requiring the medium to be flipped over halfway through the album to listen to each “side” (termed A and B, respectively). Beyond the choice of whether to listen to the first or second half of the album initially, the listener had little control as to the specific songs to be played apart from stopping or starting the record.

It wasn’t until the digital music era ushered in by CDs in the 1980s, mp3s in the 1990s and 2000s, and streaming services in the 2010s that listeners could easily choose specific tracks to listen to, or shuffle around the track list of an album. There were certain models of record players capable of track selection and shuffling by the 1980s, but they represented a small niche and, of course, were unavailable in Hammond’s lifetime.

In the grooves

A vinyl record is made by etching very thin grooves into the surface of a disc that represent the recorded audio. Since all audio can be encoded as a waveform, the unique, microscopic variations in the shapes of these grooves allow for accurate sound reproduction of the source material when a player’s stylus needle runs through the grooves. To achieve this, the disc is spun by the player at a specific speed – either 78, 45, or 33 1/3 rpm (revolutions per minute) – which pushes the tone arm to which the stylus is attached via contact with the needle. The resulting vibrations are then routed to the speakers via a preamplifier, allowing the recording to be played.

The core of the issue

However, the thin nature of a record’s grooves combined with the single color (or otherwise imprecise multicolor designs) of the disc make it difficult to determine where a given song begins or ends to the naked eye. With practice and repeat listens, one could get close, but more likely would over- or undershoot the mark by a few seconds, dropping the needle in the wrong spot.

Hammond solved this problem by devising a record that would be composed of a core of precision-cut, colored bands embedded within a transparent vinyl record. Each ring corresponded to a specific track on the album, making it possible to drop the needle perfectly at the beginning of the desired song.

E. Ray Goetz

Originally filed under the more prosaic name, “Phonograph Record,” it was renamed as the “Prisma Record” for marketing purposes. However, it appears that the unique design never caught on, despite some initial interest.

In order to solicit the invention, Hammond worked with Edward Ray Goetz, a notable music composer and theatre producer whose career spanned five decades. Goetz and Hammond first became acquainted in 1941, when the former wrote to the latter in reference to one of Hammond’s patents, though, interestingly enough, not a musical one. Hammond had registered U.S. patent #1,729,108 for a combination cigarette case and lighter in 1929, and Goetz, who had encountered such a device in France, was interested in manufacturing it for sale in the United States. However, he had come across Hammond’s patent and realized that it was too similar to the device he wanted to produce to do so without infringing on the patent. He therefore contacted Hammond – of whom he had been previously aware and wanted to meet, but had never had the opportunity to do so – in the hope of working out a royalty arrangement. He suggested they meet in person to discuss the matter.

Our archives do not record the specific responses that Hammond sent, but we do possess letters that Goetz sent subsequently that indicates that the inventor did respond, although it appears it took a little time for them to work out a meeting. It is unknown whether or not he and Hammond worked out a deal regarding the cigarette case and lighter, but it appears that they became friends and at least sometime business associates, and remained acquainted until Goetz’s death in 1954.

Why didn't the Prisma Record take off?

Correspondence between various music stores and companies and Goetz regarding the Prisma Record indicates that there was some interest in the format. Haynes-Griffin Music Shop in New York called it “an excellent innovation.” Merit Music Shops, Inc. in New York agreed, stating that it was “an excellent idea,” and echoed a comment made by Haynes-Griffin that customers complained about the difficulty of differentiating between separate tracks on records.

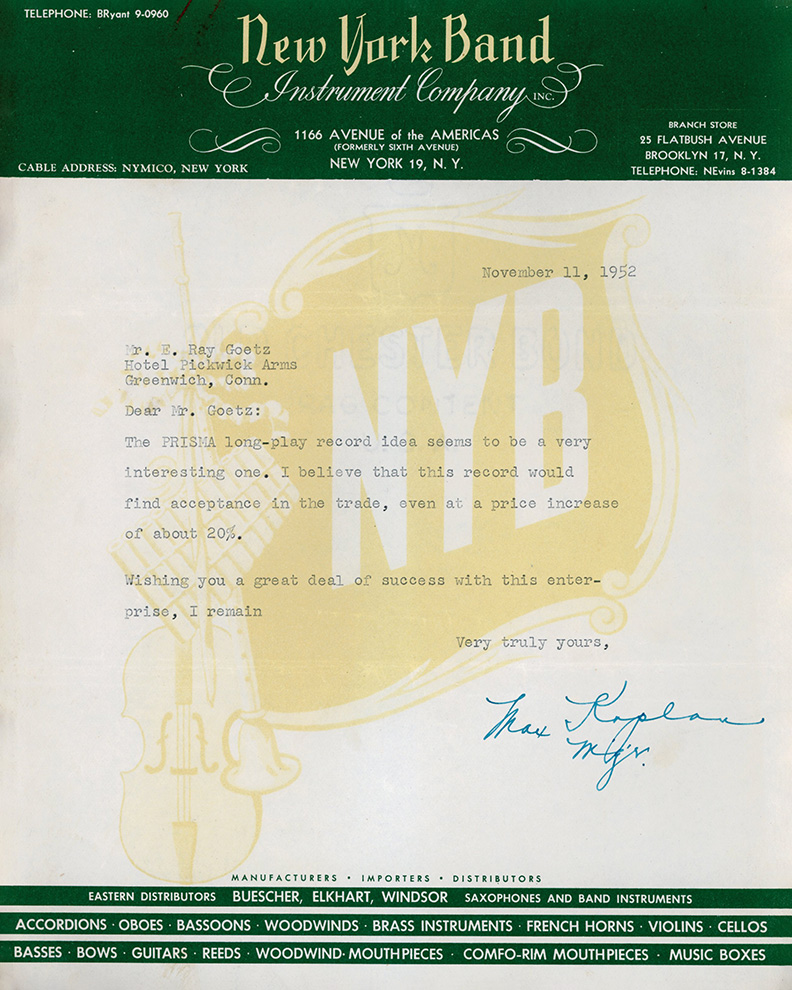

New York Band Instrument Company, meanwhile, believed it would be a hit, “even at a price increase of about 20%.” Likewise, Venture Inc., also of New York, expressed the opinion that the Prisma Record would “make for an eye-appealing piece of merchandise which the public will accept and purchase, even with a slight increase in price.”

It is worthwhile noting that most of these letters came from music retail outlets, not record labels. It is possible that Goetz and Hammond were conducting market research with this correspondence, to demonstrate to a record company – perhaps RCA, on whose board of directors Hammond served – that there was an audience for the format.

Speaking of RCA, there is an earlier correspondence from 1950 that may explain one reason why the format appears never to have made it to market. Based on a letter to Hammond from D.F. Schmit, Vice President and Director of Engineering at RCA Victor, there appear to have been some manufacturing hurdles in the record’s production. The letter was accompanied by a sample Prisma Record:

You will note in the record I am sending to you, that the plastic surface has not completely covered the edge of the core. The one we are sending you is the best we have made. Also, we have found no way to cover up the core at the center hole, which, we believe, will be very necessary in any record manufactured for sale.

Between technical challenges and price increases, the most probable explanation for the failure of the Prisma Record to take off is that it was impractical and expensive. While undoubtedly eye-catching and convenient for consumers, the record industry was booming in the 1950s, and possibly not in need of additional incentives and fancy gimmicks to encourage sales.