Hammond Family Spotlight: Harris Hays Hammond

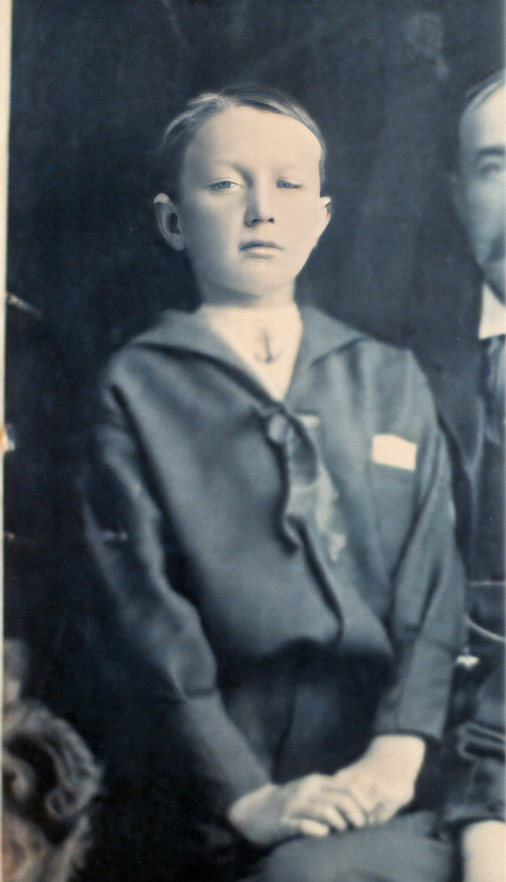

Harris Hammond (November 27, 1881-August 9, 1969)

The first of the children to be born to John Hays Hammond Sr. and Natalie Harris Hammond was Harris Hays Hammond, on November 27, 1881 in San Francisco. In October of 1882, he accompanied his mother, aunt, and uncle on a trip to visit his father in Sonora, Mexico, where Hammond Sr. was managing a silver mine. During a boat journey that escorted the family away from the country in response to political unrest and the threat of enemies Hammond Sr. had made during his tenure, Harris took ill, but, as his father recounted later on, “he turned out to be an indestructible baby.”

Harris Hammond’s future in finance was perhaps foreshadowed as an infant, according to an anecdote related by his father in his autobiography:

…my wife was in the East, visiting her sister, Mrs. J.P. Broiderick, at Jamaica Plain, a suburb of Boston. One day, as she was about to go into the city with our son Harris and his nurse, she received a check from me. She stopped in to cash it at one of the Boston banks. As the cashier did not know her, he was naturally reluctant to honor it and asked whether she knew anyone who could identify her. Unfortunately, her entire acquaintanceship was in Jamaica Plain.

The nurse, Mary Lynch… overheard the conversation… then picked up Harris, turned him upside down, and exhibiting him back-to at the cashier’s window, exclaimed belligerently, “Well, look at this now!” On the inside of Harris’s baby drawers was printed the name Hammond. The cashier honored the check, but admitted it was the first time that kind of identification had been made.

At the age of 12, Harris moved with his father, mother, brother, and aunt to South Africa, where his father had accepted a position working as a mining engineer for Barney Barnato. He was later sent to Malvern House Preparatory School in Kent, England to study, under care of a guardian, while his parents remained in South Africa. It is unclear who his guardian was, but given the school’s location, there is a slight possibility that it could have been one of the Hammonds’ English cousins, the family having been based in Kent since the 16th century, however no direct evidence of this has yet surfaced.

Following the events of the Jameson Raid in 1896, the Hammond family moved to England to rejoin their son. In the interim, Harris had a scare when a ship on which his family was originally supposed to travel – and, according to his father, had unrelated Hammonds on board – went down with the loss of most of the passengers and crew. Harris apparently saw “Hammond” in the list of victims published in a newspaper article, but was quickly assured his parents were not onboard due to a fortunate delay. Interestingly, the name of the ship was Drummond Castle, eerily similar to the name of the Museum later founded by John Jr.. Additionally, Hammond Sr. was erroneously referred to as “John Hays Drummond” on more than one occasion.

By 1899, Harris was 18 years old and ready for college. His younger brother, Jack, had also been at school in England for a few years by this point, and their father was concerned that if they spent any more time in the country, they might grow up more English than American. With that being the case, the patriarch moved his family back to the United States.

After returning home, Hammond Sr. remained very active in both political and business ventures. Harris often accompanied him on his trips across the country, and it is likely that this experience molded him into the businessman he became. He also assisted his father in his brief campaign for vice president on the ticket with William Howard Taft in 1908 in Chicago. In 1912, Harris accompanied his father and served as a secretary on a diplomatic mission to Europe sent by President Taft to commemorate and celebrate the successful completion of the Panama Canal. During this tour, he was invited by the Russian minister of credit, M. Davidov, to go on a bear hunt in the Ural Mountains, but he politely declined. In Austria, his father gave a lighthearted speech, and had it translated into German so that he might speak to his audience in their native tongue. Harris wrote back to his mother, “Father certainly created an atmosphere of humor, but I am not sure whether the guests were amused at his stories, or were laughing at his German.”

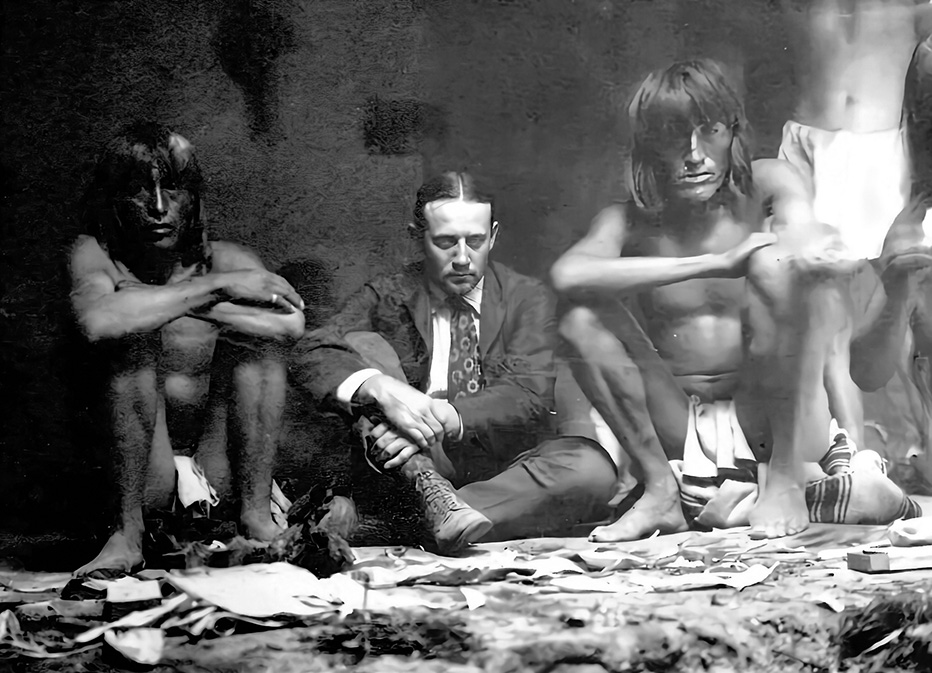

Though few photographs of Harris have been identified as yet, it is clear that he bore a strong resemblance to his father. For example, in 1916, Hammond Sr. was exploring land development opportunities in the Yaqui Valley in Mexico, and Harris accompanied him here as well. When Harris arrived to inspect the valley, he found a reception committee waiting for him. An old soldier by the name of Don Tomas Sexton was among them. According to his father’s autobiography, Harris was followed around by Sexton for a long time, which made him uneasy. Finally, the old man explained why:

“You have a secret I want to know.”

Harris replied mildly, “I haven’t any secret.”

“Yes, you have!” Sexton insisted.

“No, I haven’t! I don’t know what you’re talking about!”

“But you must have! I remember you as a young mining engineer at Alamos in 1881. You’re not a day older than you were then.”

Don Tomas believed I had drunk at the fountain of perpetual youth. At the time of this trip to Mexico, Harris was just about the same age I had been at the time of my meeting with Don Tomas so many years before.

When Harris said he was my son, Don Tomas was at first incredulous. Then a little shadow of disappointment clouded his countenance, but he took the news like the soldier he was.

Harris participated in several business ventures with his father and his brother, Jack. In 1910, he advised his father to look into oil developments in the Tampico region of Mexico; seven years later, following a two-year stint as manager of the Mount Whitney Power Company, Harris was put in charge of the oil syndicate that resulted from this tip, the Mexican Seaboard Company. His tenure was not without its difficulties, however. In 1921, a train carrying gold coins for the company’s payroll was attacked by bandits, forcing Harris to seek exemptions to local laws restricting firearms from Mexican President Álvaro Obregón so that his men could protect the company’s interests, which were granted.

At the same time as heading the Mexican Seaboard Company, Harris was made president of the Burnham Exploration Company, formed in 1919 between his father, himself, and Major Frederick Russell Burnham (1861-1947), himself a gold miner and previously an associate of John Hays Hammond in South Africa while he was under the employ of Cecil Rhodes. This venture was very successful, leading to the development of the Dominguez Hill oil field in California. In 1923, Harris proved he was his father’s son by striking liquid gold in an area of California previously thought dry. Appropriately, it was through Harris’s use of a deep-level well of 7000 feet that he found the oil deposits, much like his father had done to secure rich deposits of precious metals for Rhodes decades before.

During the De la Huerta rebellion of that same year, Harris’s financial help was sought by President Obregón, as the Mexican government was in dire financial straits and needed money to pay its soldiers. At the time, there was also a U.S. embargo blocking shipments of munitions to Mexico. His father authorized him to advance the money, and he used his political influence to urge U.S. assistance in the conflict, which was supplied, and the rebellion was defeated.

Harris later served as the president of the Laughlin Filter Corporation, a centrifuge company in New Jersey.

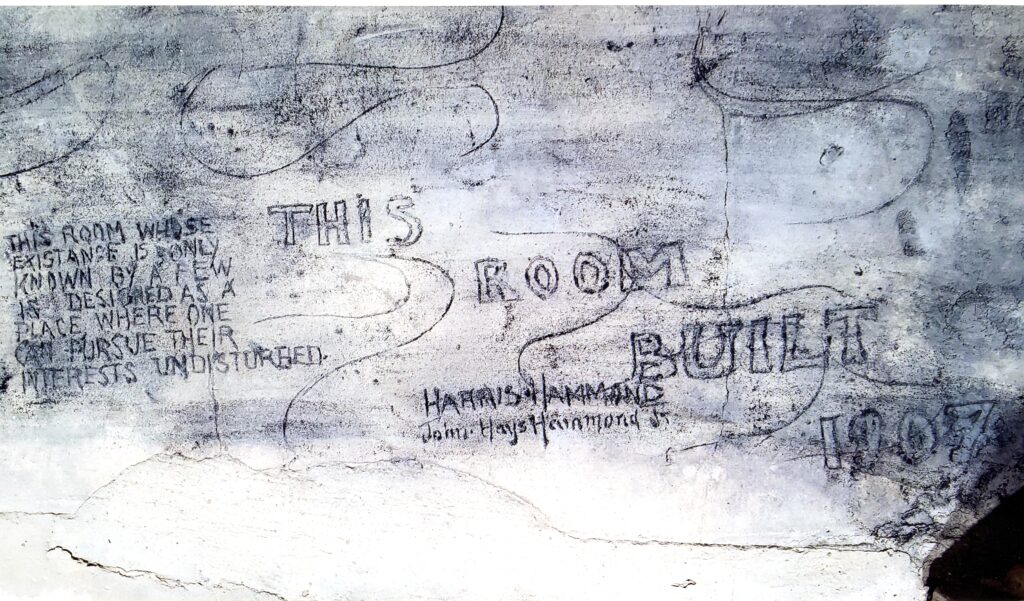

Regarding his relationship with his brother, Jack, it appears that the two were reasonably close. A recently-unearthed engraving found in the remnants of “The Bungalow,” the house where Harris and Jack lived on their parents’ estate in Gloucester, reads: “This room whose existance (sic) is only known by a few is designed as a place where one can pursue their interests undisturbed.” The room in question was built in 1907, and the marker is signed by both Harris and Jack, alongside their handprints.

Hammond Sr. relates a story in his autobiography of an experiment that both Jack and Harris conducted. They had laid a sea mine roughly 100 yards off the shore of Gloucester, which Jack would attempt to wirelessly detonate. Unfortunately, they had overloaded the mine with explosives. Harris’s job was to wait at the door of Jack’s laboratory and sound a warning to any boats that might approach too close to the mine.

Jack had trouble detonating the explosives, attempting numerous times to throw the switch with no results. He called his brother inside to help him work on the wiring of the device. When they’d finished their work, Harris was sent back outside while Jack pulled the switch a final time. Just then, Harris saw a local lobsterman with whom the two were acquainted, Joe Adams, pulling up a lobster pot right over the mine:

Just as Harris yelled to Jack, “Hold everything,” there was a terrific detonation. Joe and his boat rose fifty feet on a trumpet of water, capsized, and came down in a shower of lobster pots, boulders, seaweed, rocks, and fish.

In three jumps Harris reached the rowboat at the foot of the little cliff and battled his way out among the waves to rescue Joe who was splashing about in a half-drowned condition. Harris hauled him in, thankful to see he was not hurt.

When Joe had partially caught his breath, he gasped, “God-amighty, did you see what happened to me? I went up right on top of a big wave.”

“Nonsense, Joe,” Harris said. “We’ve been watching you for the last quarter of an hour. I saw you lean over to pull in that lobster pot and you fell in.”

“But I felt it,” Joe insisted. “My boat’s all broke up! As I went up, I could see right over the top of the house.”

“You’re crazy,” Harris insisted, this time with some show of justice, since the top of the house was a hundred feet above the water line. “You must have kicked the boat as you fell. I think you’ve had a few too many drinks.”

The people of Gloucester heard the noise of the explosion but thought it was probably blasting in the near-by Rockport quarries. The boys comforted Joe and bought him a new rowboat.

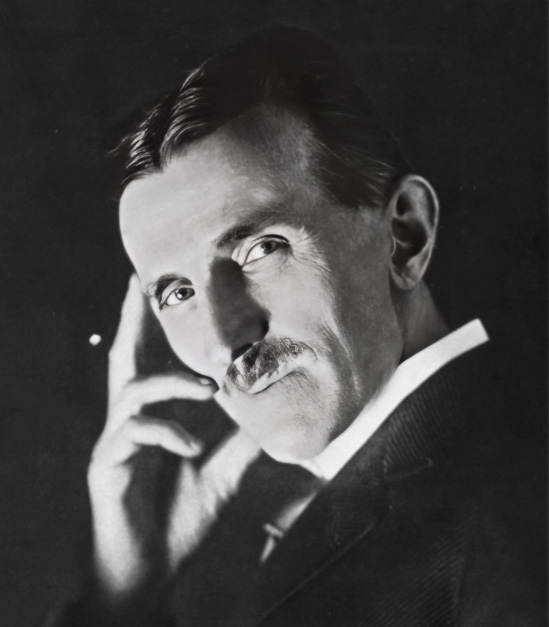

Harris also participated in the financial aspects of his brother’s scientific work. When John Hays Hammond Jr. approached famed inventor Nikola Tesla about a partnership in developing wireless technology in 1910, he was cautioned by his father, who was acquainted with the scientist, “Go in on this with your brother Harris. He is older than you and more experienced. And be careful with Mr. Tesla. He tends to spend gold as if it were copper.”

As part of their business arrangement, several thousands of Hammond dollars went into funding Tesla’s bladeless turbine, which he was having difficulties developing. After requesting additional funds in the amount of $10,000 (over $300,000 in today’s money) from the Hammonds, Harris sent him the following reply on June 10, 1913:

Dear Mr. Tesla,

As you know, we have advanced a great many thousands of dollars in the development of this turbine and have expected each week the past year to be in a position to have tested it…[Now] we find that the turbine is only partially set up at the Edison plant…[We are missing] a splendid opportunity of having it thoroughly and honestly tested by people who would be the greatest benefit to us should these tests be successful.

Source: Wizard: The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla by Marc Seifer (1996)

Tesla did not take well to this letter, replying, “…if I were dealing with a man less attractive to me than yourself, I would disdain to answer.”

In spite of his business acumen, however, Harris Hammond’s finances were not always stable. In the early 1930s, Harris was a director of Acoustics Products Company, later Sonora Products Corporation, a manufacturer of high-quality phonograph and radio products. The company ended up filing for bankruptcy, and Irving Trust Company became its receiver. Irving ended up suing Harris and the other directors, charging that they had diverted company profits from stock sales into personal accounts.

Years of legal wrangling followed, during which time Hammond Sr. passed away and left assets to Harris in a trust fund. Ultimately, Harris was ordered to pay Irving Trust Company $1,838,755 in penalties (almost $50 million in today’s money). At the time, Harris earned $20,000 per year (just under $450,000 today), not including his inheritance. He argued that he could not pay the judgment from funds from the estate of Hammond Sr. because they were held in trust. The bank apparently suspected that this was part of why the elder Hammond had placed the funds in a trust in the first place, as these legal proceedings had been in place since 1931.

In order to pay the funds, it was decided that Harris would have an income garnishment of $1,160 per month (around $26,000 today), amounting to $13,920 per year (roughly $310,000 today), leaving him with a net income of $6,080 per year ($135,000 today). It would have taken Harris 132 years to pay this debt at that rate.

The equivalent of a $100k+ salary in today’s terms might not sound so bad, but Harris protested nonetheless. He maintained that he owed $2,400 in Federal and State income taxes (a little over $52,000 today), $9,133 per year for his apartment ($200,000 today), and $12,000 per year for household expenses ($262,000 today). Added together, this would have been $23,533 per year in expenses ($514,000 today), against a salary of $20,000. Taken at face value, this meant that Harris was apparently already operating at a deficit of $3,533 per year (over $77,000 today). To comply with the garnishment, then, would have meant that he would been in the red by $17,453 per year ($381,000 today), making his expenses nearly double his actual income. It is no surprise, therefore, that he appealed this amount.

In August of 1937, Judge John C. Knox reduced the garnishment order to $160 per month (about $3500 today), amounting to $1,920 per year (just under $42,000 today). In a TIME Magazine article dated Monday, August 16, 1937 it was noted that at that rate, Harris would square his debt “in 957 years and eight months. Irving Trust Co. would collect its last cent in the year 2895 A.D.” Given that neither Harris nor Irving Trust Company still exist, however, we have to assume that his account has been settled.

In March of 1941, Harris evidently met Walt Disney, as referenced by the latter in a note to John Hays Hammond Jr.: “At a dancing party the other night I met your brother and his wife and we had quite an interesting chat.” Since Richard Hammond never married, Disney could only have referred to Harris and his wife Elise, who were based in California at the time.

Despite not grabbing exciting headlines like Jack or Natalie Hammond, or applying himself to creative endeavors like Richard, Harris was still an important member of the Hammond family. As the eldest son, he was perhaps the most responsible and serious-minded, and less inclined to seek the spotlight.

While Harris had no children, like his siblings, he did marry Elise between 1910 and 1920. He passed away on August 9, 1969 at the age of 87 in Los Angeles.