Hammond Family Spotlight: Natalie Hays Hammond

Natalie Hays Hammond (1904-1985)

Born in Lakewood, New Jersey, where the Hammonds had a home, on January 6, 1904, Natalie Hays Hammond was the last of the children born to John Hays Hammond Sr. and Natalie Harris Hammond.

The Last Hammond

Natalie was also the last Hammond from a line that began with John “Hamon” of Nonington, Kent, in England (1475-1526) in the 15th century, during the second reign of King Edward IV (r. 1461-1470; 1471-1483). Historical accounts differ, but sometime between 1526 and 1555, a manor was purchased at Estwall (aka Esole, later known as St. Alban’s Court) by either John or his son, Thomas Hamon, who also appears in genealogical records as Thomas “Hamond.” The modern spelling, “Hammond,” appears to date from the generation of Thomas’s great-great-great-grandson, John Hammond, born c. 1668.

It was this John Hammond (the great-great-great-great-great-grandfather of Natalie Hays Hammond) who migrated to what would later be known as Annapolis, Maryland in 1685, splitting the Hammond family into American and English lines.

The English Hammonds’ estate at St. Alban’s Court remained in the family through 1938, when the widow of Captain Edgerton Hammond (1863-1923) sold the property at auction, her son, Second Lieutenant Douglas William Hammond, having been killed during WWI in 1915 at the age of 18.

The American branch of the Hammond family tree would endure for another 70 years past the tragic pruning of the English branch, however, with Natalie Hays Hammond living until 1985.

If this discussion of the Hammond family’s ancestors seems tangential, it should be noted that some of the information was collected by Natalie herself, in a family tree she designed, which still hangs in Hammond Castle Museum.

But the Hammond daughter’s interests did not end with genealogy. Indeed, she was every bit the renaissance person as her more famous brother, Jack, if not more so. Natalie’s life and career spanned eight decades, during which time she explored numerous avenues of work and interest, and won accolades to match.

Natalie's Early Years

Natalie wanted to make an impact on the world from the time she was a child. She inspired her mother to create the War Children’s Christmas Fund during WWI, having expressed the wish that her Christmas gifts be given to war refugee children in Belgium and France instead of her.

Natalie accompanied her family to Europe on multiple occasions. At the age of six, she went to the United Kingdom with her family to attend the coronation of King George V. In 1924, she traveled with her parents, and again made acquaintance with King George and Queen Mary.

Natalie also made international friends – for example, she went to school with Loutfia Yousry, the daughter of a former Egyptian minister to Washington. Later in life, she was asked by Loutfia to be a bridesmaid at her wedding in Egypt. It was during this time that the young woman caught a glimpse of an unfamiliar culture, and she recounted it vividly to her father. This experience may have sown a seed for the young woman’s later interest in art and iconography from nonwestern cultures.

Hammond Sr. taught his young daughter woodcraft, and often went swimming, sailing, and fishing with her while in Gloucester, Massachusetts. A fishing boat was later named in her honor by Captain Lemuel Spinney, alongside one named for her father; the daughter’s namesake was the faster vessel in a direct competition, much to Hammond Sr.’s chagrin.

The first inklings of her art career began at the age of six, when she took up drawing. This was encouraged by her parents. Two years after this, she turned to writing, penning The Adventures of Sir John Hammond, inspired by her father, complete with illustrations.

The Multipotentialite

Natalie was not content to live the superficial life of an average socialite. She committed herself seriously to a study of the arts, and refused to confine herself to any one medium. Drawing, painting, sculpting, woodcarving, needlework, and costume design were all fair game. In today’s parlance, she might be called a “multipotentialite,” having developed her talents in numerous arenas.

It must be emphasized that Natalie was no hobbyist: not only did she hold several exhibitions of her artwork to effusive critical acclaim, but she also ran her own business by the age of 24: the Natalie Hammond Process Company. It was through this company that she marketed a unique form of applique, which could reportedly metalize any object, including fabric. While she was the inventor of this process, she never patented it, apparently preferring to keep it a trade secret. In contrast to her brother, Jack, she held only one patent: a 1936 design patent for a (literal) clamshell pocket watch, which she created for celebrity jeweler Paul Flato.

"I don't see how a person can justify being alive if he doesn't work."

By the end of 1930, Natalie reportedly had 1500 employees at her company. When asked why she insisted on working when she could have easily led a comfortable life of leisure instead, she explained, “It’s in the blood. I just had to do it. What’s a girl to do if she’s the innocent victim of heritage? There’s no escape for her. So here I am!” She considered work the most important thing in her life, and once commented, “I don’t see how a person can justify being alive if he doesn’t work.”

Natalie was regarded by some in the press as a curiosity in her day. Very much a modern woman, her independence, talent, and ambition set her apart from many of her contemporaries. That said, she also worked with other notable women of the age, such as Martha Graham and Alla Nazimova on Broadway productions, and also worked in the early film industry. Her skills as a costumer and a miniaturist were especially renowned in her early career.

"I ask only the privilege of planning my life in my own way."

One of Natalie’s most ambitious projects consisted of a trio of unusual architectural designs, including a domed, stained glass church (or apartment house), an innovative dance theater, and an impressive 80-story skyscraper consisting of many glass and aluminum towers. None of the buildings were ever constructed, but models were exhibited in 1932.

Though the number is unverifiable, Natalie was reportedly engaged seven times in her life, but never married. This is unsurprising, given the views she laid out in an interview published in 1931:

When I was a debutante I decided that marriage delayed until the thirties had a better chance of survival… At thirty-five men and women are beginning to learn their tastes and capabilities. I had the courage of my convictions. I have never met a man with enough ambition, imagination and humor to make me change my mind.

The 25-year-old artist and businesswoman bristled at repeated inquiries about her marital plans, and ended the interview with the following: “I am a spinster, if you will, but a completely happy person… I ask only the privilege of planning my life in my own way.” In the 21st century, this might not seem like a radical sentiment, but it was quite unusual for women to be so uninterested in marriage in the 1930s. It could be argued that Natalie’s wealth gave her the luxury of singledom, but it could also be argued that she was an early feminist. Additionally, evidence suggests that Natalie may have had romantic relationships with other women, which could explain why she never married a man.

The Massachusetts Women's Defense Corps

As World War II broke out in 1939, Natalie Hays Hammond was inspired to travel to the United Kingdom to help with a civilian defense program, but her efforts failed. Undeterred, she founded the Gloucester Civic Patrol in the early 1940s, organizing schools to teach young women vital skills they might need should there be a direct attack on American soil. She later established the Women’s Civilian Defense School in Boston through the Massachusetts Committee on Public Safety.

The school offered classes on topics ranging from radio communication to emergency transportation. The schools quickly evolved into the Massachusetts Women’s Defense Corps, an organization with thousands of members. Natalie transformed the group into a paramilitary outfit, and either was appointed, or appointed herself, colonel. Speaking of outfits, the uniforms she and her fellow members wore were evidently quite lavish, having been designed by Abercrombie & Fitch. The M.W.D.C. also began publishing a monthly newspaper in 1942, to report on the doings of the organization.

"An attitude of arrogance?"

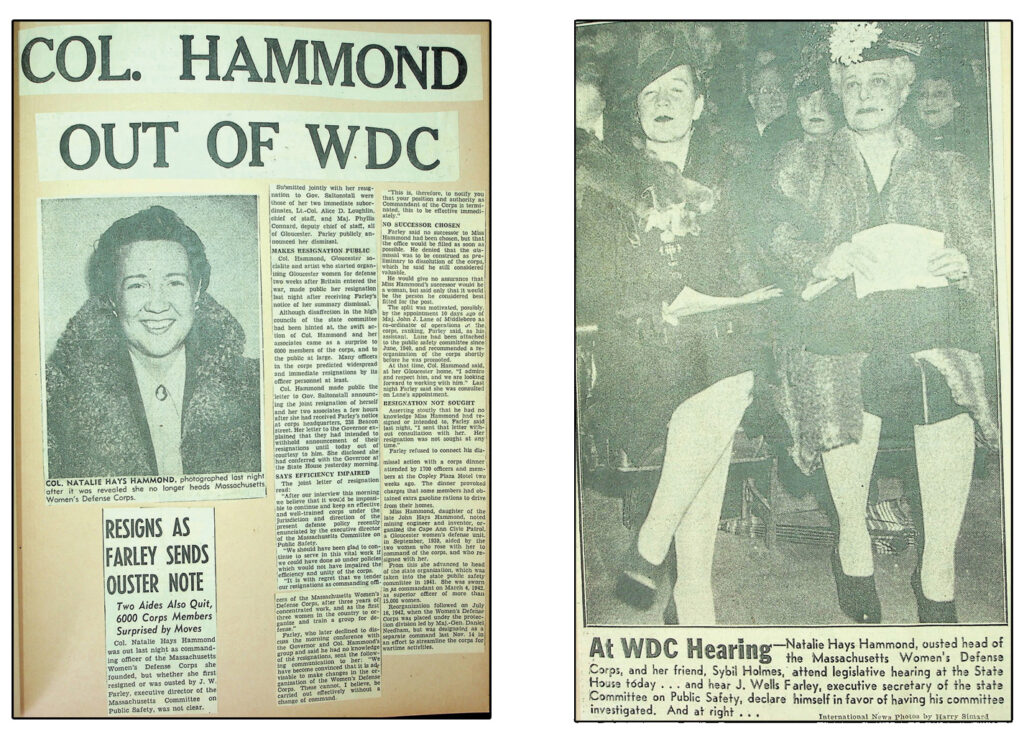

By 1943, however, such state-based, semi-military organizations were made increasingly obsolete by a stronger national defense effort with broader wartime powers. Controversy arose when additional funding was solicited from the state legislature, which opponents of Hammond believed was excessive. Due to increasing pressure, Natalie resigned her position with the M.W.D.C. in that year, and the group was eventually dissolved. Accounts of the time state that she was essentially forced out, however. The battle over funding may have served as an excuse for her opponents within the Committee on Public Safety to neutralize Natalie’s increasing power and influence. The language used to justify their disapproval hints at a possible gender bias, with accusations from male leaders that she assumed “an attitude of arrogance” that forced her dismissal, however this is only one interpretation.

Natalie's Later Years

In the postwar years, Natalie continued her art and authored multiple books, including the innovative New Adventurers in Needlepoint Design. In 1957, she established a new residence in North Salem, New York, which would become the still-extant Hammond Museum and Japanese Stroll Garden. She was honored for this in 1979 with the Medallion Award of the Westchester Community College Foundation. In the early 1960s, she also offered advice to her brother on running his own museum, and he, in turn, was on the board of hers.

After the deaths of her siblings in 1965 (Jack), 1969 (Harris), and 1980 (Richard), she was the last of the Hammonds. Having never married or had children, her passing on June 30, 1985 marked the end of a 500-year-long dynasty that still reverberates today.