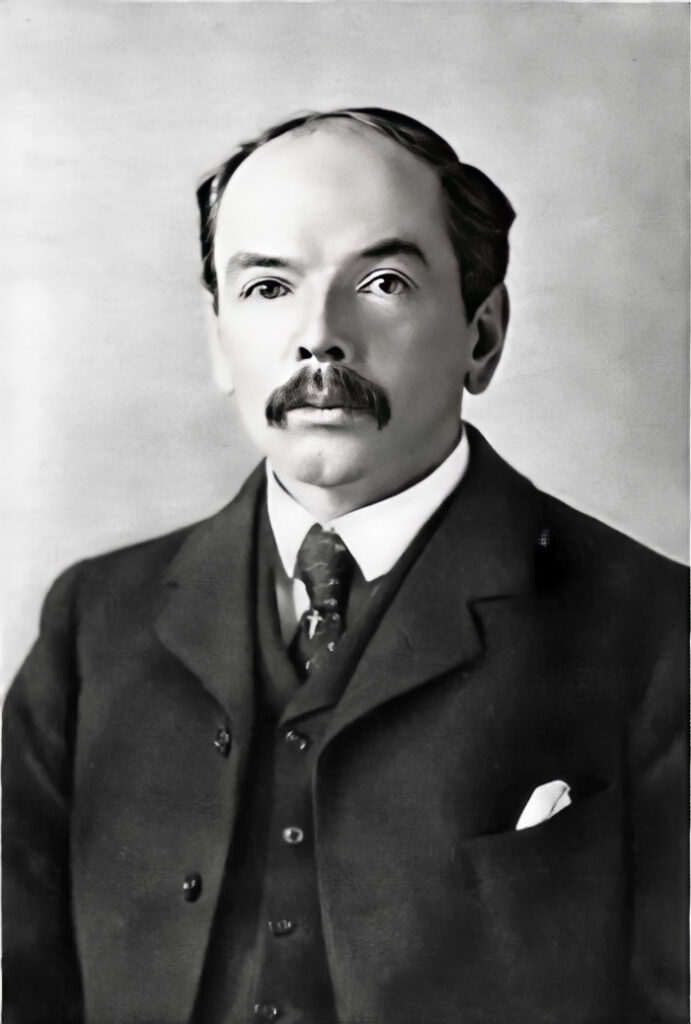

Hammond Family Spotlight: John Hays Hammond Sr.

John Hays Hammond Sr. (March 31, 1855-June 8, 1936)

John Hays Hammond Sr. was the father of John Hays Hammond Jr. A famously wealthy man, Hammond made the family fortune through his expertise and consulting in silver, gold, and diamond mining industries.

Born in 1855 in San Francisco, Hammond’s boyhood was spent in the Old West, in the shadow of the gold rush of 1849. His father, Richard Pindell Hammond and his uncle, John Coffee Hays, were both well-respected and accomplished soldiers who would prove to be very influential in the early development of San Francisco and the surrounding areas, and held various government positions during their careers.

Eventually, Hammond went east to attend college at the Sheffield School of Science at Yale University, where he son, John Hays Hammond Jr., would eventually follow in his footsteps. It was here that he first met William Howard Taft, future U.S. president and chief justice of the Supreme Court, a connection that would eventually deepen decades later. Hammond later went on to study at the prestigious Freiberg University of Mining and Technology in Germany, where he met his future wife Natalie Harris. They married following their return to the United States, and had their first child, Harris Hays Hammond, in 1881. Following this, Hammond managed mines in both Mexico and later Idaho, and in both positions he encountered conflicts with labor and episodes of violence, though he survived them.

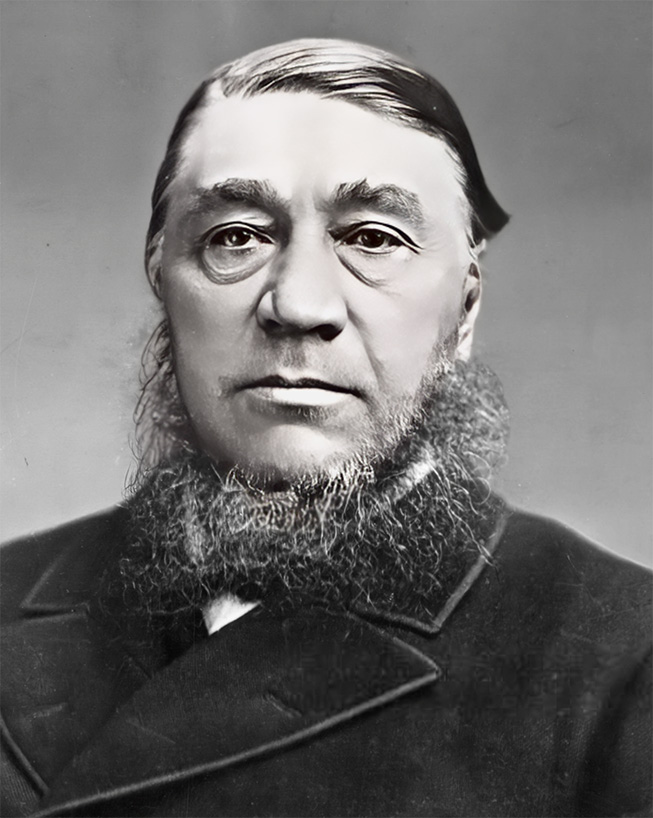

Hammond eventually traveled to South Africa in 1893 to accept a position with mining magnate Barney Barnato, but his tenure with him was short due to a difference of professional opinion. Soon after, Hammond accepted a position managing the lucrative mines of Cecil Rhodes’ British South Africa Company based in Johannesburg. It was at that point that he became fatefully embroiled in local politics in what was then known as the Transvaal.

Both British and American mining interests felt excluded from the political process in the South African Republic, despite being responsible for most of its economic development. Possessed of the belief that they were better suited to control the affairs of the government and economy than the Boer government under President Paul Kruger, Hammond, Rhodes, and Rhodes’ associate Leander Starr Jameson hatched a scheme to seize the levers of power there by rallying the American and British mine workers to support their cause under the purported banner of a democratic impulse inspired by the American Revolution.

The conspiracy and attempted coup were a disaster. The lack of enthusiastic support from the mine workers was enough to doom the project, but it was made worse by Jameson’s impetuous jumping of the gun in deciding to march a fighting force towards Johannesburg in support of a manufactured rebellion that had failed to materialize without being signaled to do so. Since Jameson also neglected to cut the telegraph lines to the city in his haste, he and his men were discovered, intercepted, and captured by Boer forces. This debacle was later known as the Jameson Raid.

The involvement of Hammond and the other ringleaders was discovered thanks to the presence of a prewritten letter discovered on Jameson’s person that explicitly called for his aid, which was signed by Hammond and others. The doctor had requested this to serve as justification for his intervention, to make it later appear that he was responding heroically to a call to action rather than invading the South African Republic. Unfortunately for Hammond and his comrades, since the rebellion that was supposed to summon Jameson didn’t actually exist, the existence of the letter proved that the entire operation had been a sham.

Hammond and three other leaders of the so-called “Reform Movement” were imprisoned for months (during which time they were visited by none other than famed author Mark Twain) and sentenced to death for their parts in the attempted coup, though this was later commuted to the paying of hefty fines in the wake of international pressure for leniency. The Jameson Raid is considered to be an important prelude to the Second Boer War (1889-1902) and impacted South African politics for decades to come.

Following this debacle, Hammond moved his family to England for a few years, and it was during this exile that his third child, Richard Pindle Hammond was born. The Hammonds then returned to the United States at the turn of the 20th century, where the engineer secured a lucrative position as a consultant for the Guggenheim family’s enterprises. Hammond later became involved in American politics, striking up a strong relationship with his old school chum William Howard Taft. Hammond briefly ran as a candidate for the position of Taft’s vice president in 1908 (presidential and vice presidential nominees were nominated separately at this time), but received little support and much criticism, and ended up in an informal role as part of the president’s “Golf Cabinet.” His influence, however, led some to consider him a “shadow” vice president. He was also acquainted with several other notable U.S. presidents, such as Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, and Warren G. Harding.

Later in his life, Hammond was a founding member of several organizations promoting world peace. He believed that the key to this was the foundation of a world court of some type. Such efforts laid the foundations for the serious consideration of such an idea, and at least indirectly led to the eventual foundation of the International Criminal Court.

At the time of his death in 1936, Hammond Sr. left a sizable estate and a complex-yet-celebrated legacy in the public imagination.