The Jameson Raid

Introduction

The Jameson Raid was undoubtedly the biggest debacle with which John Hays Hammond Sr. was associated in his long career. What began as a fireside chat between three men in the South African wilderness ended in an international incident that would damage reputations, finances, and careers alike. More importantly, it set the stage for a war that affected the course of South Africa’s history for a century.

Background

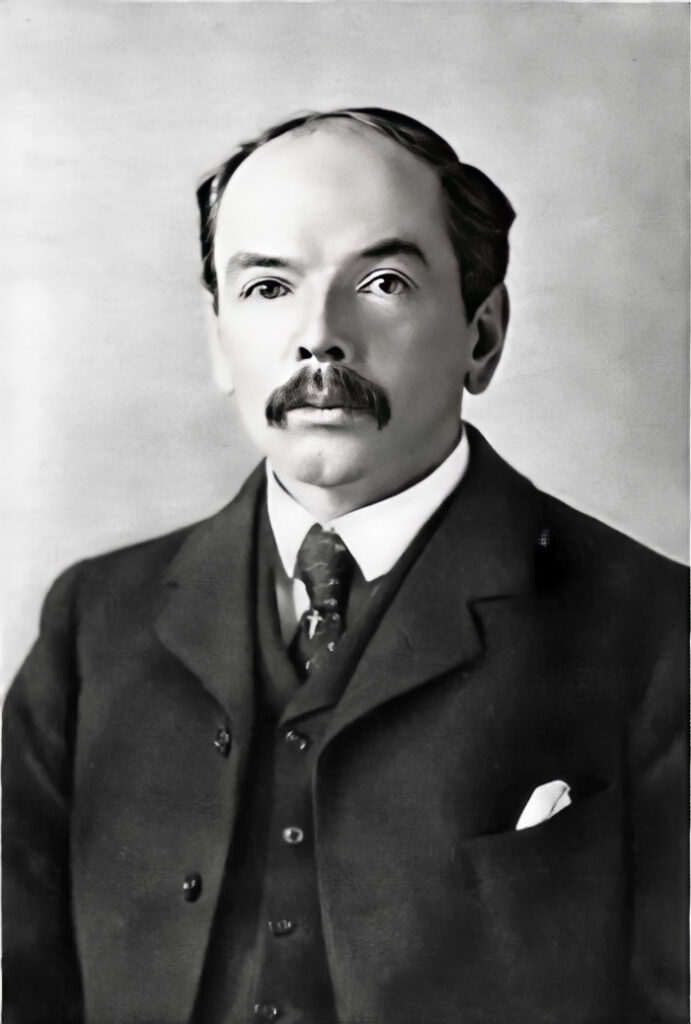

In 1893, fresh off of an eventful and contentious stint as the manager of a silver mine in the Coeur d’Alene valley in Idaho, John Hays Hammond turned his sights to South Africa and its booming gold and diamond mines. Having established himself as a capable mining consultant with years of experience in North America under his belt, he desired to improve his fortunes across the Atlantic.

Hammond first went to work for Barney Barnato (1851-1897), a British financier and Randlord. The term “Randlord” came from “The Rand,” which was itself short for the Witwatersrand, a 35-mile-long ridge in what was then known as the Transvaal, or the territory consisting of the South African Republic and the Orange Free State. This ridge was known for its vast gold deposits, and those who successfully capitalized on its wealth, like Barnato and Hammond, reaped rewards worthy of the “lord” moniker.

While the relationship between Barnato and Hammond was largely cordial, the latter soon found a greater opportunity with the former’s main rival, Cecil Rhodes (1853-1902). Rhodes, one of the preeminent British Imperialists of the age, had made a fortune in South Africa in the diamond and gold mining industries, and had parlayed his wealth into great power, managing to become Prime Minister of the Cape Colony along the way. His British South Africa Company colonized what became known as Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe and Zambia), which was named in his honor.

The legendary career of Rhodes is far too broad in scope to summarize here, but what is relevant is that the “Big Man” in South Africa saw value in Hammond’s expertise as a mining engineer. For his part, Hammond recognized that Rhodes was a man of vision, and that aligning himself with the magnate’s interests would see his own fortunes rise meteorically. It also did not hurt that Hammond was an Anglophile, for all his idealization of the rugged individualism that characterized the American West of his upbringing.

"A Nose for the Mines"

Hammond’s true genius as a mining consultant was his uncanny ability to accurately assess the mining potential of a given land stake. It was not just that he had a “nose for the mines,” but that he was able to sniff them out deep underground. Surface mining techniques like open pit mines were and are still used, but the price for acquiring lands with shallow ore deposits was steep in South Africa at this time, on the order of around $40,000 per acre. To put that into perspective, the equivalent of that amount today would be $1 million on the low end, and possibly much higher in the context of the economy as a whole.

Open pit mining is far easier and less hazardous than underground hard-rock mining, which accounts for why land that could be mined in such a way commanded such high prices. Nevertheless, Hammond’s previous experience taught him that the profit potential of the latter was several orders of magnitude greater than the former. Hammond knew that deep-level mining was the key to controlling the mineral wealth in South Africa. An acre of land that might have little to no mineral value close to its surface went for far less money than its mineral-rich equivalents. In some cases, such parcels could be had for as little as $10 per acre (only a few hundred to a few thousand dollars in today’s money), which meant that Rhodes could acquire the mineral rights to massive stakes of land, provided he was willing to delve around two thousand feet below the earth to strike gold. The logistics and costs of the mining itself would be more complicated, but the benefits far outweighed the downsides.

This advocacy of deep-level mining and the knowledge and experience of how to extract valuable minerals efficiently were the single-greatest contributors to John Hays Hammond earning his initial fortune, and ensured a fruitful working arrangement with Cecil Rhodes. It elevated Hammond to the ranks of the Randlords, and he moved his young family (including John Hays Hammond Jr.) to live with him at his South African mansion.

But that, apparently, was not sufficient for the ambitions of Hammond, Rhodes, and their allies in the booming gold mining industry. In The Cowboy Capitalist (2017), Charles van Onselen paints a vivid picture of Hammond’s involvement in what became known as the Jameson Raid, arguing convincingly that he was its architect.

Hatching the Plot

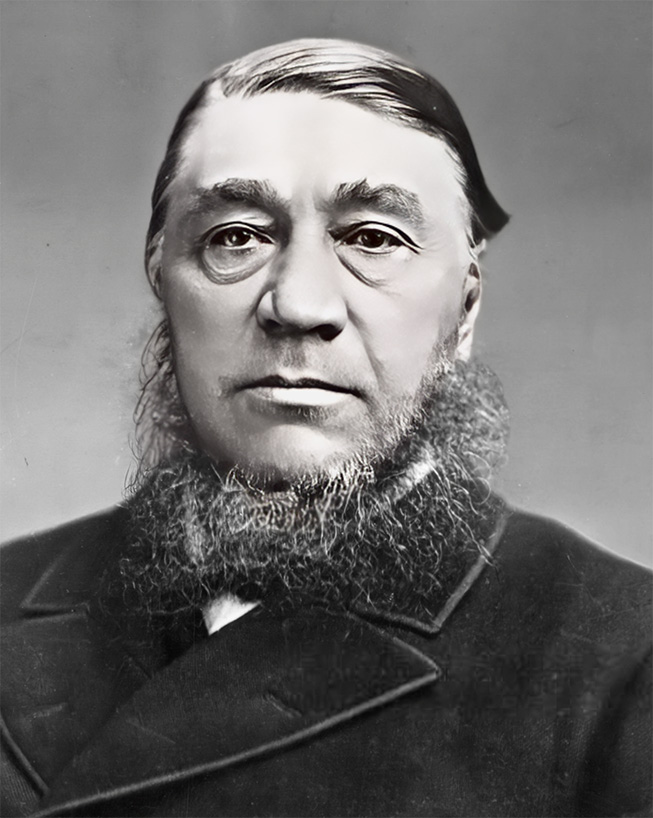

Traditionally, the historiography of the Jameson Raid was viewed through a British lens: Rhodes cooked up a scheme to seize power from President Paul Kruger (1825-1904) with the aid of Leander Starr Jameson (1853-1917), a Scottish doctor who met Rhodes while practicing medicine in South Africa. Establishing a close relationship with the magnate, Jameson eventually became involved in his colonial enterprises. He traded medicine for military campaigns and established a heroic and adventurous reputation.

But through careful scholarship, Charles van Onselen argues that the American John Hays Hammond was the true mastermind behind the failed “revolution,” citing, among other evidence, the Hammond and Hays families’ southern origins and their adjacency to the 19th-century practice of “filibustering.” In modern parlance, this term refers to a legislative maneuver involving extended speechmaking in order to delay proceedings or make a political point, but originally the term derived from “freebooting,” a term for pirating or lawless adventuring. In this context, filibustering consisted of unsanctioned American military expeditions into foreign territories, particularly those led by Southerners like William Walker, into Latin American regions to establish colonies there. The basic blueprint of a filibuster bears remarkable similarities to what was planned in South Africa in 1895.

The thesis is that John Hays Hammond, in collaboration with Rhodes and Jameson, designed a scheme which, the three hoped, would result in foreign dominance over the South African Republic – dominance that would have a British and American flavor. The plan was to stoke a rebellious fire in the hearts of the “Uitlanders” (or outlanders – i.e. foreign workers in South Africa), leading to them uprising against Kruger’s Boer-led government.

The Boers were the descendants of largely Dutch-speaking peoples who had settled in South Africa beginning in the 1600s. While not native to the continent, they held the lion’s share of political power in the Transvaal. There existed a history of tensions between the Boers and the British colonists, which had already resulted in one military conflict, the First Boer War (1880-1881), a result of British incursions into Boer territories. This ended largely in the Boers’ favor, as their independence was recognized by the British, although with some concessions that maintained British influence.

A turning point, however, was the discovery of gold in the Witwatersrand. This made the Transvaal even more appealing to British interests, including Cecil Rhodes. If Rhodes (and by extension, Great Britain) controlled the Transvaal politically, he could consolidate his power financially and thereby expand the British Empire. Jameson, for his part, agreed philosophically with Rhodes, and naturally Hammond had a lot to gain personally through his association with a Rhodes monopoly over the gold and diamond trades in South Africa.

Stoking the Flames

In order to promote a revolt, however, there had to be some justification beyond naked greed for resources. The stated aim of the conspirators (who soon expanded beyond the original trio and later called themselves “The Reform Committee” to soften their image as insurrectionists) was always publicly expressed largely in political terms, despite their underlying economic motivations. In short, their belief was that the policies of Kruger’s government were disadvantageous and hostile towards the Uitlander population. The crux of the argument was that the foreign workers and their employers contributed the most to the economy of the South African Republic, and yet they received no real political rights in return.

One example of this disparity was the fact that an Uitlander had to reside in the republic for 14 years before being eligible to vote; this was seen as an unreasonably lengthy and burdensome prerequisite. That Cecil Rhodes himself had taken steps to disenfranchise the indigenous African population of his own Cape Colony by raising the wealth requirement for voting was an irony the Reform Committee seemed to ignore. In addition, foreigners were heavily taxed with the South African Republic, and the government held a monopoly on commodities and infrastructure vital to the mining industry.

The general tone of the public grievances of the “Reformers” appeared to be fundamentally republican in nature. They were not unlike arguments used by the American colonists during the War of Independence (e.g. “taxation without representation”). This American influence also bears the stamp of Hammond, who took pains to draw parallels between his cause and that of his nation’s founders. However, to whatever extent Hammond and the other leaders of the movement genuinely believed in the validity of their political complaints is less relevant than their core motivation: securing a monopoly on the South African mineral industry. President Kruger’s Boer-friendly policies presented an impediment to that goal, and so, to them, he had to go.

But what of the average working Uitlander? Did they share this dissatisfaction with the Boer government? As it turns out, not especially, or at least not to an extent necessary to support a full-blown rebellion. The local economy was doing reasonably well at this time, despite some recent hiccups, and there was therefore little incentive to change the status quo. Hammond and the other leaders may or may not have believed otherwise, but it was clear that they would have to manipulate public opinion in order to stir enough embers to support a coup. There were public propaganda campaigns through the local press, and firearms were smuggled into the republic in preparation for a general uprising. The extent of these preparations is too complex to elaborate upon in detail within this article, but the point is that there were preparations – in other words, this was an organized, orchestrated attempt to overthrow Paul Kruger’s government by force.

Preparing for Revolution

Another preparation, and the most fateful one, was that Leander Starr Jameson and a contingent of fighting men were dispatched to Bechuanaland (today Botswana) to await a call to arms. The plan was to light the spark of rebellion within Johannesburg, then call for “aid” from Jameson via a prepared letter written prior to the events of the Raid. Jameson himself requested this letter be written as a way of covering up his premeditated involvement in the conspiracy. Hammond was one of the cosigners.

The intention was to paint Jameson in a heroic light befitting his reputation. If he were seen as riding to the aid of a popular uprising, his noble image would stay intact, and perhaps they would even succeed in their cause; however, if he were to march towards Johannesburg without first being summoned, the move would be seen as an invasion in support of a foreign-led coup instead. But numerous problems developed that led to the latter scenario.

As stated previously, there was relatively little appetite for an uprising among the Uitlanders. Not even all of the leaders of the so-called Reform Movement agreed that a violent takeover of the government was necessary. As rumors started to reach the government’s ears about the planned uprising, the ringleaders started to get cold feet (hence the pivot to “reform” instead of “revolution”). Beyond that, there were several delays in preparedness, with only a fraction of the smuggled arms available at the time of the Raid. Finally, the leaders of the movement were still debating what form a new government should take should the coup prove successful.

The Raid Begins

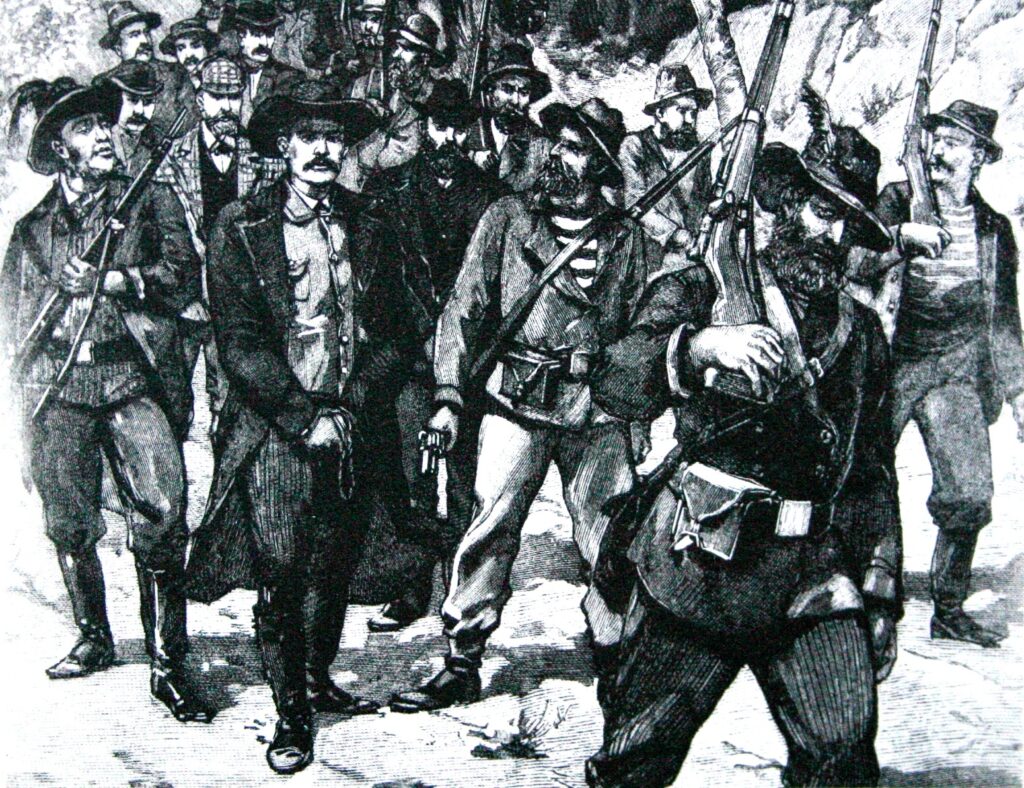

When recounting the events leading up to the Raid, for the remainder of his life, Hammond consistently maintained that he specifically instructed Jameson to take no action until he received word from him expressly. Jameson, however, had a reputation as being somewhat impetuous. He and his men were tired of waiting in perpetual standby in the bush, and by December 29, 1895, he had finally lost patience. He led his forces over the border from Bechuanaland, thereby officially beginning the Raid.

The plan might yet have been salvaged but for the failure of his forces to cut the telegraph lines to Johannesburg. Spies had observed Jameson’s premature movements, and sent word to Kruger’s government. As a result, the Boer forces were soon marshaled against him, and they forced his surrender at Doornkop on January 2, 1896. During his arrest, the letter he had requested was found on his person, with the filled-in date of December 29, 1895. Given the timeline and the fact that there had not been, in fact, any popular uprising that would have justified such a call to action, the existence of the letter implicated Jameson and the other conspirators in the plot.

The Raid Ends

The ringleaders were rounded up and initially imprisoned in what by all accounts were poor conditions, even by prison standards. Hammond and a few other high-ranking members of the committee, including Frank Rhodes, brother of Cecil, were put on trial and officially sentenced to death for their roles in carrying out the attempted overthrow of the government. That said, it is probable that the sentences were never actually intended to be carried out, given that an alternative judgment consisting of hefty fines and public contrition was proposed shortly thereafter. The judge’s verdict was possibly part of a gambit to scare the conspirators into accepting the profitable alternative, with Kruger’s clemency an added public relations bonus. However, Hammond and the other three members facing the gallows refused to recant their plot, insisting that it was not a matter of money, but of principle.

Intriguingly, at one point, Hammond and his fellow prisoners were visited by none other than famous American author Mark Twain, who was touring the area at the time. Notably, his account of the visit corroborated the unsanitary conditions of the prison. Negotiations continued for several months, during which time Hammond’s health failed him. At various points, the prisoners were allowed respites in more comfortable environments for medical reasons, with Hammond under house arrest temporarily.

During this tense time, John Hays Hammond Jr. (aka “Jacky”) was seven years old. Later in life, he could only recall dim memories from the ordeal, such as silver-booted soldiers standing guard outside his home, and he does appear with the soldiers in at least one archival photograph, dressed in military garb himself and holding a gun. At one point, he was playing in the yard, digging a hole, when a sudden explosion terrified the boy. Believing that he had “dug up Hell,” the blast was, in reality, a factory explosion nearby that resulted in many casualties.

Meanwhile, Natalie Harris Hammond turned to international diplomatic channels, seeking aid from officials as prominent as U.S. President Grover Cleveland to put pressure on the South African Republic to release Hammond. She also sought clemency from Kruger directly, who formed a positive impression of the woman for her loyalty and intelligence.

Legacy of the Raid

Ultimately, cooler heads did prevail, and Hammond and his comrades were released later in 1896 on payment of stiff fines and a promise to stay out of South African politics for several years. Hammond’s fine was paid by Cecil Rhodes specifically, out of the large salary he owed to the engineer.

The Jameson Raid was an embarrassment for those involved in its planning and disastrous execution. Hammond’s relationship with Jameson was badly damaged thereafter, and the engineer blamed the doctor for botching the campaign for the remainder of his life. They eventually managed to have civil interactions in the future, given that their professional connections to Cecil Rhodes endured, but it was never as cordial as it had once been. Rhodes himself was subjected to heavy public and political scrutiny in Britain for his role in the debacle, and was forced to resign from his position of Prime Minister of the Cape Colony as a result. Nevertheless, Rhodes remained active in England and South Africa until his premature death from heart disease in 1902.

For his part, Leander Starr Jameson ended up surprisingly well despite his name being attached to the Raid. After serving a few months of a 15-month prison sentence in England for his actions (he was released early for medical reasons), he later returned to South Africa and was even elected to his friend Rhodes’ old position as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony in 1904. He was also honored with a baronetcy in 1911, and passed away in 1917, his body buried near Rhodes’ grave in the Matopo Hills in what is now Zimbabwe.

As for Hammond, he moved his family to England at the tail end of 1896, where they resided until 1899, before moving back to the United States, eventually to own an estate in Gloucester, Massachusetts. His infamy due to the Jameson Raid spread far beyond the Transvaal, and his reputation in the United States suffered as a result. It is theorized that this was the reason for his move to London, to allow time for the controversy to pass and rehabilitate Hammond’s public image. However, that period did sow the seeds in the mind of young Hammond Jr. to eventually build his castle home and Museum, as he was first exposed to the vestiges of medieval European architecture there. Therefore, indirectly, it is possible that this Museum may never have existed had his father not been involved in this messy South African adventure.

Positive as that fact may be for this organization, the consequences of the Jameson Raid were anything but beneficial for the future of South Africa. The event turned up the heat on simmering tensions between the British Empire and the Boer republics, which culminated in the Second Boer War (aka Anglo-Boer War) from 1899-1902. The result was decidedly less favorable to the Boers than the first war had been, with President Kruger fleeing the country to live out the remainder of his life in exile, and Britain establishing the dominance over South Africa that would eventually lead to the horrors of Apartheid. While it would be historically irresponsible to lay the blame for all that came after at the feet of John Hays Hammond Sr. alone, without his involvement in the Raid, the history of South Africa may have been quite different.